[Note: this article originally appeared on The Epoch Times in March.]

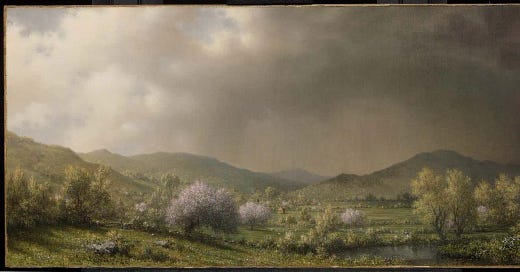

In my part of the world, the first hints of green are beginning to tinge the fields as life wells up from within the earth. Spring fast approaches.

This delightful time of year has always captured poets’ imaginations, and there’s no better way to celebrate the season than to read some of their meditations—preferably outside.

Here are three great spring poems to get you started.

‘Lines Written in Early Spring’ by William Wordsworth

Wordsworth’s “Lines Written in Early Spring“ is a rich mixture of sadness and sweetness, joy and sorrow. The speaker begins by capturing the unbounded joy of spring when the landscape begins to flush green and all the birds trill songs in harmony, filling the land with music. “I heard a thousand blended notes/ While in a grove I sate reclined.”

The delight of this season, when the earth regains her youth and dances before us in bursts of sunlight and flowers, is immediately tempered by the next two lines: “In that sweet mood when pleasant thoughts/ Bring sad thoughts to the mind.” Here, the speaker establishes the paradox of “sweet” and “sad” that runs through the rest of the poem.

In the third stanza, Wordsworth begins to elaborate on this mixed mood. The poet sets up the swelling freshness and innocence of “Nature” (a word he capitalizes, to personify it) as opposed to the sorry state of humanity. In the words of poet Carol Rumen, “In ‘Lines Written in Early Spring’, nature and mankind are linked but stand for contrasting modes of being.”

This theme of contrasting nature’s purity with humanity’s corruption is one Wordsworth often reflects on in his work. In “The World is Too Much With Us,” he laments the fact that humanity is so busy with profit and industry that it loses touch with the unlimited wealth of nature’s beauty and peace. In that poem, after several lines of beautiful natural imagery, Wordsworth wrote, “For this, for everything, we are out of tune.” Humanity isn’t in sync with nature.

In “Lines Written in Early Spring,” nature’s harmony—symbolized by harmonious, blended birdsong—is contrasted with the disharmony of the human world.

To her fair works did Nature link

The human soul that through me ran;

And much it grieved my heart to think

What man has made of man.

This last line, which returns at the end of the poem as a gloomy refrain, falls heavy on the ear. The repetition of sounds in “man” and “made” and “man” is almost overbearing, monotonous, and the tongue stumbles over them. Although Wordsworth doesn’t define what, exactly, “man has made of man,” the context of his other poems sheds light on it. The heavy rhythm of the line is suggestive of man’s coarse insensitivity to the riches of nature and the needs of his fellow man.

After the plodding line about humanity, however, the poet jumps to the spritely activities of the birds that “around [him] hopped and played.” He sees ecstasy coursing through the natural environment of animals and plants: “But the least motion which they made/ It seemed a thrill of pleasure.”

While humanity has become deadened in its everyday routines, the wild things described in the poem have an almost feverish energy and a joy that spills over. The speaker asserts that even the budding twigs experience pleasure in unfurling their leaves.

‘From You I Have Been Absent in the Spring’ by William Shakespeare

In this sonnet, Shakespeare praises and celebrates both the season of spring and an unnamed person, generally thought to be the “Fair Youth” who appears in a number of Shakespeare’s sonnets. The poem’s basic structure is this: The speaker, lamenting the absence of the Youth, can’t enjoy the glories of spring because they remind him of the absent loved one. To him, spring still feels like winter.

This poem stands as an interesting contrast to Wordsworth’s. Where the speaker in Wordsworth’s poem compares humanity unfavorably with nature, the speaker here sees nature as a poor substitute for the human person and its beauties a mere shadow of his friend’s.

But there’s a kind of playfulness going on here, too. The speaker insists that the delights of spring have made little impression on him (in the absence of his friend) while, at the very same time, elaborately and eloquently describing those delights. Clearly, spring has made an impression on the poet.

First, he notes how “April dress’d in all his trim/ Hath put a spirit of youth in every thing.” He touches on one of spring’s mysteries: the mystery of renewal, rebirth, and youth, which maybe doesn’t strike us forcefully because we’re so familiar with it. The cyclical return of life to the landscape that appeared so totally and finally dead during the beleaguered winter months is nothing short of miraculous.

In Shakespeare’s sonnet, this youthful spirit is so miraculous that it makes even “heavy Saturn” laugh and leap. This is quite a feat because, as literature professor Oliver Tearle pointed out, “the planet whence we derive the adjective ‘saturnine’, denoting heavy and sullen sluggishness – is cavorting about with the springtime.”

What follows is a litany of the features of spring, all presented—paradoxically—as failing to arouse the poet’s notice in the absence of his friend. The speaker includes appeals to multiple senses, mentioning the “lays [songs] of birds,” the “sweet smell” of various flowers, the “lily’s white,” and the “vermilion in the rose.”

The poet concludes, “Yet seem’d it winter still, and, you away/ As with your shadow I with these did play.” Here we have a speaker who is out of sync with nature’s rhythms. Shakespeare dramatizes the truth that a person’s inner life often functions at odds with his or her outer surroundings.

‘Spring’ by Gerard Manley Hopkins

Where Wordsworth and Shakespeare’s meditations on spring stir up melancholic and lonely thoughts, Hopkins finds in the season an impetus to religious joy.

Using his signature “sprung rhythm” and explosive, energetic use of rich sound combinations, Hopkins bursts forth:

Nothing is so beautiful as Spring –

When weeds, in wheels, shoot long and lovely and lush;

Thrush’s eggs look little low heavens, and thrush

Through the echoing timber does so rinse and wring

The ear, it strikes like lightnings to hear him sing;

The creative, vivid imagery comes so thick and fast it’s easy to miss it. The alliteration in “long,” “lovely,” and “lush” of line two slows readers down and elongates the line, just like the grass it’s describing. The “sh” of “lush” is also a soothing sound not unlike the sound made by wading through tall grass.

Next, the speaker turns to the birds, choosing unexpected verbs to describe how their songs strike the ear: “rinse and wring.” These verbs evoke the idea of a cleansing, refreshing sound that washes the ear clean—a brilliant way to describe how the notes of birdsong in early spring rejuvenate us after the muffled sounds of winter.

All this talk of the clear, fresh, blue sky fills readers with a sense of light. It seems to naturally raise the poet’s mind to heavenly and religious things as he continues,

What is all this juice and all this joy?

A strain of the earth’s sweet being in the beginning

In Eden garden.

The poet is asking, Why is nature so full of zest and joy this time of year—the zest and joy recognized, too, by Wordsworth and Shakespeare and virtually all great poets? How to account for it? Hopkins’s answer is that it’s a kind of echo of the primordial paradise of Eden, before sin brought sorrow into the world.

In the next lines, he plays with sounds, sound combinations, and recombinations in a frolicking way: “Have, get, before it cloy/ Before it cloud, Christ, lord, and sour with sinning.” The reference to Christ suggests that something of the joy of Eden is recuperated through Him.

The poem’s final lines are an almost wordless, ecstatic barrage of sound expressing the joy of innocence—whether the innocence of Eden or the innocence of redemption or both isn’t entirely clear, yet the speaker profoundly associates it with the joy of spring: “Innocent mind and Mayday in girl and boy / Most, O maid’s child, thy choice and worthy the winning.”

“Maid’s child” likely refers again to Christ and his virgin birth. Hopkins concludes with the idea that the recovery of spring-like innocence was worth the Incarnation.