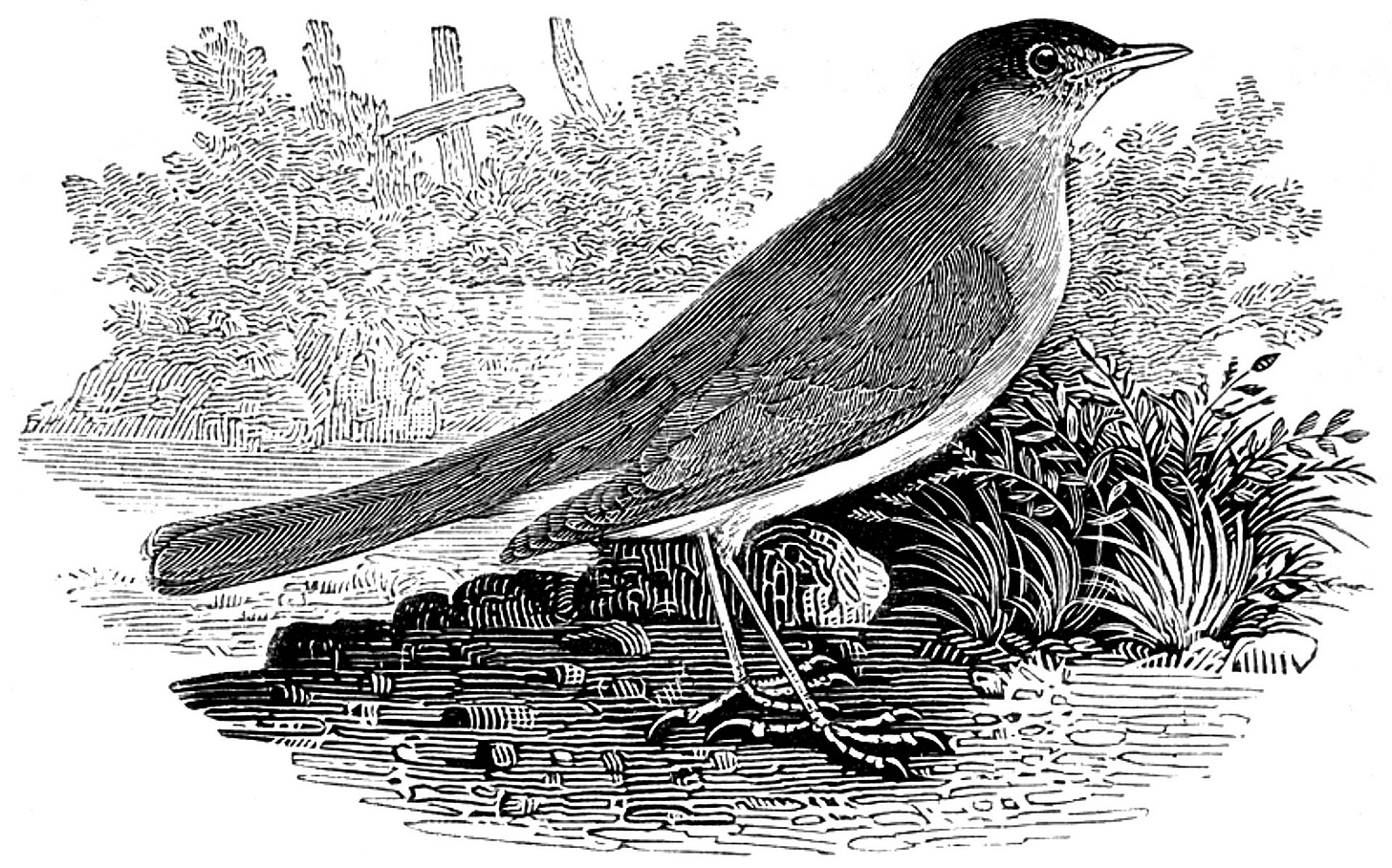

Critics have debated whether the death Keats longs for in “Ode to a Nightingale” is an actual death or a symbolic “death” of creative fulfillment. I argue that it’s wrong to view this death in the sixth stanza as a symbol for the climax of creativity only—it is more than that, and comes closer to representing an actual death. The language throughout the poem and also in Keats’s other works point to a desire for an actual death as a way to disappear into the world’s beauty and escape from life’s pain. By the end of the poem, however, the poet realizes that this death would mean the loss of the beauty he has been celebrating, and the desire dissipates.

Critics such as Al-Khader misread the poem when they posit that the mood of the poem does not fit with the idea of bodily death. Al-Khader argues, “The…death [of line 55 is] related to poetic ecstasy and not bodily death because the mood of the poem and the poet’s joy is contrary to the idea of physical death” (3). With this statement, Al-Kahder seems to have missed the poem’s undertones. The poem is haunted by a note of sadness, not joy, especially as it relates to mortality and humanity’s susceptibility to suffering. The language of the poem is meditative and often melancholic. For example, the opening lines of the poem are not words of “the poet’s joy” but rather of sorrow: “My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains / My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk, / or emptied some dull opiate to the drains / One minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunk” (lines 1-4). The mentioning of hemlock, a poison, and the Lethe, one of the five rivers of the underworld, are but two of many references to mortality and physical death throughout the poem. The fading away into “the forest dim” of line 20 conjures up images of escape from the world, the “deep-delved” earth of line 12 suggests a grave, while the “incense,” “embalmed,” and “requiem,” of lines 42, 43, and 60 respectively, bring to mind a funeral. These images indicate almost a kind of death-wish—not necessarily in a despairing way but as the expression of a deep longing for something transcending the mortal world. Though Keats withdraws somewhat from this death-wish by the end of the poem, as I will demonstrate, these images of mortality permeate the work. They are not images of joy. In this way, the mood of the poem is entirely in keeping with the idea of physical death.

When Al-Kahder mentions the “poet’s joy” he may be referring to the consolation the poet seems to find in the nightingale’s song, but the poet is enchanted by the happiness of the nightingale not because he, too, possesses such carefreeness, but precisely because he does not. The poet wishes to “fade far away, dissolve, and quite forget / What thou among the leaves hast never known, / The weariness, the fever, and the fret” (lines 21-23). These are not the words of a poet “full of joy” in the usual sense. The poet’s only joy in the scene comes from the consolation of the bird’s song and the natural beauty around him. This consolation is only needed because the poet has real sorrow he wants to forget.

Al-Kahder misjudges the issue when he later references another critic, Battern, and asserts that Keats is too immature to be able to write about actual death. Al-Kahder writes: “I think Battern (1998) was right to reject the idea of physical death because Keats was too young to write so knowingly of death’ (p. 236)” (3). Here, Al-Kahder and Battern alike seem to have forgotten that Keats was actually well-acquainted with death in spite of his young age. Keats’s father died when Keats was 8, his mother died when he was 14, and his brother died after a long illness when Keats was 23 (ODNB). All of this death surrounding Keats is likely to have had a profound impact on him and forced him to mature swiftly. Further, the loss of so many loved ones lends credence to the idea that real, actual death was often in Keats’s thoughts and poems. And to assert that a young poet must be too immature to write about death is to ignore the fact that Keats may have been experienced beyond his years.

In the poem, Keats views death as “rich” because he sees it as an escape from suffering and a way to dissolve into the natural beauty that surround him. Al-Kahder writes “Logically, how can it be ‘rich to die’ (l. 55) if it were ordinary death?” But Al-Kahder has misread this element of the poem. Ordinarily, death is viewed as the greatest evil, so on the surface Al-Kahder’s point seems valid. But through Keats’s poetic lens, death becomes something entirely different. At this point in the poem, Keats sees it as an escape from pain and a unification with beauty. He writes, “for many a time I have been half in love with easeful Death…Now more than ever seems it rich to die, / to cease upon the midnight with no pain, / while thou art pouring for thy soul abroad / In such an ecstasy!” (lines 55-58). Keats calls death “easeful” because it would release him from life’s cares and sufferings. He would find it rich to die while the nightingale is singing because the nightingale’s song embodies natural beauty. At the moment of death, the poet would be surrounded and absorbed into the song, i.e., the beauty of the natural world. Keats’s longing for death is a response both to the pains of life as well as its beauty, a beauty which Keats perhaps feels is too beautiful to bear, as the nightingale is “too happy” in its happiness (line 6). Keats longs to “leave the world unseen” and dissolve into its beauty, the beauty of the nightingale’s song. Critic Jalal Kahn observes, “This is a death Keats has been longing for since early in his poetic career. In Sleep and Poetry, he expresses his wish to ‘die a death / Of luxury’ in the midst of the intoxicating earthly pleasures” (88). Kahn indicates that the desire for an “easeful death” is present throughout Keats’s career, and the quotation from Sleep and Poetry again reinforces the idea that Keats wanted to die amidst beauty. These facts lend support to an interpretation of the death in “Ode to a Nightingale” as an actual death.

Lines 59-60, however, mark Keats’s withdrawal from this longing for death. Keats writes, “Still wouldst though sing, and I have ears in vain— / To thy high requiem become a sod.” Here, the poet realizes that this death would mean for him the loss of all of the beauty and richness of the world that he has just been celebrating and resting in. Though he would indeed dissolve into that natural beauty in a very literal sense—become “a sod,” a part of the earth—he would at the same time become inert to the nightingale’s “high requiem,” unable to hear or appreciate it anymore.

“Ode to a Nightingale” is an intense musing on beauty, suffering, and real, physical death. The tone, word-choice, and mood of the poem as well as Keats’s biographical context support the interpretation of the death in the poem as a physical death, not a symbolic one. Finally, we see in lines 59-60, the poet’s realization that this longed-for death would result in the loss of the beauty he has been mediating upon. In response, the poet withdraws from this desire for death.

Works Cited

Al-Khader, Mutasem T. Q. “Keats’ ‘Ode to a Nightingale’: A Poem in Stages with Themes of Creativity, Escape and Immortality.” International Journal of Art and Humanities, vol. 1, no. 3, 2015, pp. 1-8. http://ijah.cgrd.org/images/Vol.1No.3October2015/1.pdf.

Keats, John. “Ode to a Nightingale.” The Norton Introduction to Literature, edited by Kelly Mays, Norton, 2016, pp. 854-56.

Khan, Jalal Uddin. “Keats’s ‘Ode to a Nightingale’: An Appreciation in Keatsian Aesthetics with Possible Sources and Analogues,” Dogus Universitesi Dergisi, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 77-96. http://oaji.net/articles/2016/670-1469709388.pdf.