[This article originally appeared on The Epoch Times.]

There’s an object in my house that is over 500 years old. It’s a leaf from a French medieval illuminated manuscript Book of Hours, dating from about the year 1500.

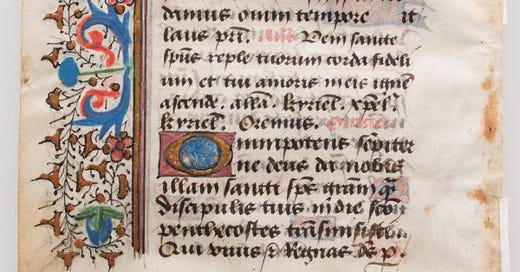

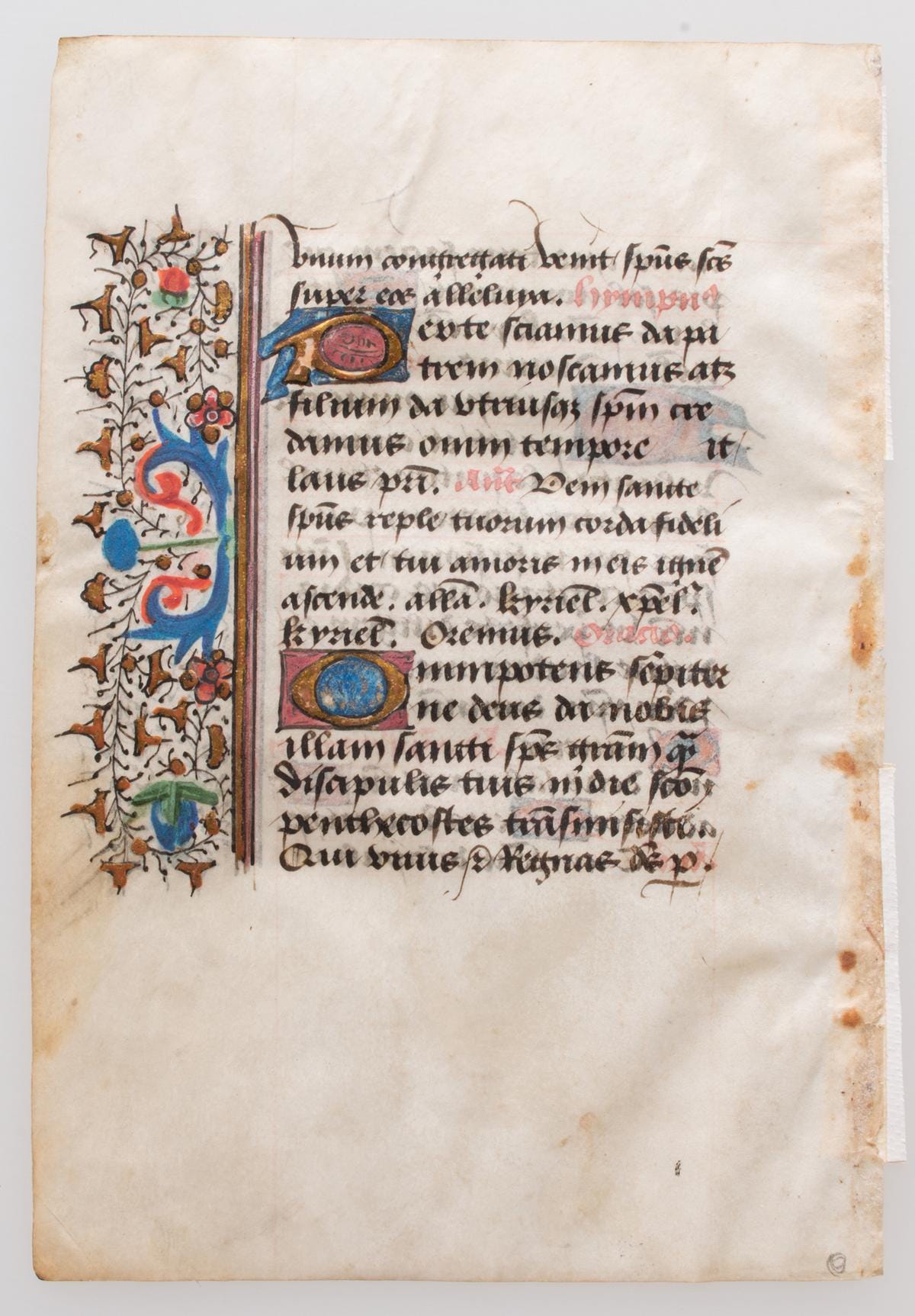

It’s small. That was the first thing I noticed about it when my wife gave it to me as Christmas present last year. But its smallness, neatness, and fineness of work only add to its beauty. And in this 4 1/4-inch by 2 7/8-inch piece of parchment, small enough to fit in the palm of your hand, are whole worlds of history and religious devotion.

A View to the Past

Manuscripts are among our chief sources of information on medieval life. As Raymond Clemens and Timothy Graham write in “Introduction to Manuscript Studies,” “Parchment is literally the substrate upon which virtually all knowledge of the Middle Ages has been transmitted to us.”

Even the process itself of making medieval manuscripts reveals something about the age from which they hail. It was a long, painstaking, and expensive process to make a book. First, scribes—who were often monks—needed a substance to write on, and this was usually parchment, made from animal skin (of calf, sheep, or goat, most commonly). The hair on the skin had to be loosened by submerging the skin in lime water for up to 10 days, after which it could be scraped off. Then, the parchment maker would stretch the skin very tightly while scraping further to thin the parchment, a process that took several more days, before leaving it to fully dry. Once dry, the skin could be removed from its frame and cut into sheets. And here we see the medieval interest in permanence, for all of this labor was in order to make something lasting: Parchment can endure for more than 1,000 years.

A combination of powders was needed to make the surface of the parchment receptive to ink and other materials. The sheets of parchment were formed into gatherings of 16 to 20 pages. The skins used in manuscripts sometimes contained flaws, scar material, or insect bites, which could result in holes in the finished parchment. In my manuscript leaf, for example, a diminutive hole can be seen in the parchment along one margin, but, in my opinion, this only adds to the charm and authenticity of the piece.

With the parchment all prepared, the scribe was now ready to begin the actual writing process. He wrote with feather quills that were washed, hardened with heated sand, and then shaped at the end into a point. Black ink could be made from “gallnuts” (growths on oak trees) or by mixing soot with a binding agent. With these materials ready, the scribe could then copy the text. If he made an error, it could be scratched out with a knife and then written over.

It’s interesting to note that most of the books worked on in medieval scriptoriums were copies of existing texts. In the first place, there were no printing presses, so hand-copying was the only way for a work to proliferate and be read by many people. In the second place, medieval people had great respect for tradition and less interest in originality than we have today, so they spent a lot of time preserving and copying what they would have considered the classics. Even when medieval writers did write original pieces, they often drew from existing source material, such as oral legends. This may have been the case with the medieval Anglo-Saxon poem “Beowulf.”

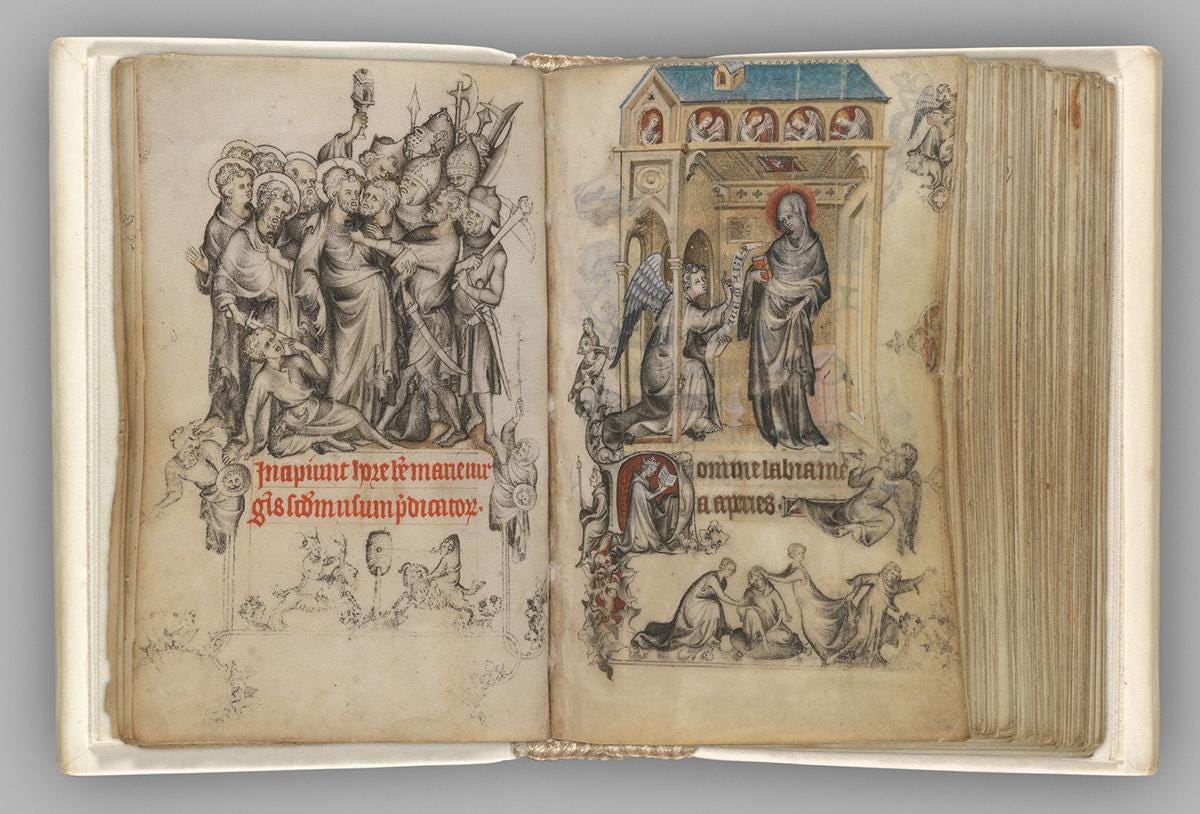

Once the copying of the text was complete, the illuminator’s job was to beautify the manuscript using precious metals and paints. Perhaps most famously, illuminators used gold leaf to make the pages of the book shimmer and come to life. This was applied by putting down a glue-like substance and then breathing on the gold leaf, which gave it just enough moisture to adhere to the page.

Paints came from a variety of remarkable (and rare) substances: minimum (orange), lapis lazuli (blue), cinnabar (red), woad plant (dark blue), sea mollusks (purple), squid (dark brown), and even the larvae of scale insects of the genus “Kermes” (yielding a much-sought-after red), according to Clemens and Graham. All of these paints were used to create the illustrations, patterns, and illuminated letters we see on manuscripts. The intricate organic patterns and vibrant colors that adorn medieval manuscripts are one of the most famous and celebrated works of medieval art and culture, and understandably so.

The final step of the process was to bind the finished gatherings into a book. The binder would sew the gatherings together and attach them to leather strips, which, in turn, were laced through tunnels that had been carved in wooden boards (the front and back covers). The whole thing was then covered with leather, which might be further decorated with silk, velvet, or gold.

What emerges from the picture of the scribe or illuminator or binder bent over his work, day after day, working, often enough, by candlelight, is a sense of how important these books must have been to the people who made and owned them. These books were their treasuries of wisdom, faith, and delight, and it’s often been noted that in the dark and chaotic days following the collapse of the Roman empire, the scriptoriums and libraries of monasteries on the misty islands of Europe’s fringes preserved much of the learning of the West.

The Book of Hours

My manuscript leaf dates from much later, of course, near the end of the Middle Ages. It’s from a Book of Hours, which was one of the most popular books of the late Middle Ages. As Clemens and Graham explain: “Originating around the middle of the thirteenth century and retaining their popularity well into the sixteenth, they were made in the thousands for royal, aristocratic, and middle-class owners. Frequently commissioned to mark a marriage, they were often treated as heirlooms.”

But what were they? In a word, they were prayerbooks. They were designed for the laity to follow the regular schedule of daily prayer of monks and priests, known as the Divine Office. The page framed on my bookshelf comes from the middle of a hymn of thanksgiving called the “Te Deum.” It’s written in Latin, of course, the universal language of prayer at the time, but in English it says, in part, “The glorious choir of the Apostles, the wonderful company of Prophets, the white-robed army of Martyrs, praise Thee.”

This particular book was likely crafted for a lady. When I look at the manuscript, I can’t help wondering about this lady. Who was she? What were her fears and hopes and dreams? What was the manner of her life and of her death? She must have been relatively wealthy to afford to commission a book, given the rare materials, long hours, and careful craftsmanship involved.

How many generations, I wonder, have looked at this very page, read it, perhaps prayed from it, seen in it “wrought in the monk's slow manner, / From silver and sanguine shell, / Where the scenes are little and terrible,/ Keyholes of heaven and hell,” as G.K. Chesterton puts it in “The Ballad of the White Horse”? And at what high points of these people’s lives might they have turned to this very page, which is part of a hymn of thanksgiving, to offer their gratitude to God through song?

I can’t know, of course, but when I hold the little sheet of parchment, I feel stories welling up from its surface, stories of men and women facing struggles and triumphs not so different from my own, at their core, stories of men and women whose legacy has, in a mysterious way, passed into those little, delicate marks, the red and blue and the bits of gold that gleam with an otherworldly light.