The Line

The Dangers of Postmodernism and Neo-Marxism in the Universities

In 1903, famous black writer and intellectual W.E.B. Du Bois wrote in The Souls of Black Folk that “the problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line—the relation of the darker to the lighter races of men in Asia and Africa, in America and the islands of the sea.” Du Bois was a civil rights activist and the first African American to obtain a doctorate from Harvard. His opinion carried some weight. Evidently, it still does, for there are many, especially in the academy, who seem to still believe this, to still insist that race and racism are the biggest and most important issues of our day.

I attended a public university, so I know this to be true first-hand. During my time there, I attended a race studies class that was masquerading as a literature course taught by a neo-Marxist professor. How the study of literature, which is supposed to be about the good, the true, and the beautiful, became a vehicle for Left-wing ideology is a long story. It has to do with the almost millennia-long decline in Western intellectual life since the triumph of Nominalism, which eventually (centuries later) led to Structuralism and Deconstruction and a general Postmodern nihilistic skepticism. All of these are philosophies that attack the meaning of words and the belief in the possibility of underlying truth behind language.

Because modern philosophy jettisoned a belief in truth, language itself, and therefore literature, became meaningless. What can be learned or appreciated in a work of literature if truth, beauty, goodness, do not exist? This question must have slowly dawned on academia after its Faustian bargain with Postmodernism. Realizing that there was no longer any truth or beauty or wonder to be found in literature, according to their own philosophy, academics had to come up with something else to do in the field of literary studies. At the same time, other ideologues were eager to usurp literature for their own ends. The confluence of Marxism with Postmodernism and its injection into higher education helped to provide a grotesque “solution” and create the Postmodern/Relativist/Marxist zombie that now dominates our classrooms across America. Marxism, which took the Postmodern abandonment of objective truth as a given, gave literature and other academic fields that used to be concerned with truth a new goal: the analysis and exposure of power dynamics. Marxism sets aside truth and concerns itself simply with power, oppression, and revolution—the raw “realities” of materialistic human existence.

Of course, classical Marxism is rare in the academy today, but its fundamental obsession with the oppressor/oppressed binary (applied to varying groups) has taken hold and flourished. Thus literary studies are now largely concerned only with analyzing how a work of literature exposes, participates in, or repudiates some existing power dynamic. There is nothing else to analyze for those who don’t believe in truth. All that remains is a dark, Darwinian view of human existence as an endless grappling between groups that seek to dominate one another, and the role of the academic is to expose the tactics of the current “oppressor” in order to bring about “justice” (whatever that means to someone who disbelieves in transcendentals).

But back to my college. In the literature course in question that I was taking, we were discussing Nella Larsen’s Passing, a novel centered on race and a perfect platform for the professor to launch a dialogue on racism.

At one point during the class, the professor and the other students began to bemoan the fact that we feel the need to specify race when we are discussing a black man, but not when we are discussing a white man. As one student put it, “If I see a black man trip and fall on the stairs, I’d say to you, ‘A black man just fell and needs help.’ But if I see a white man trip and fall on the stairs, I’d just say, ‘A man needs help.’ We just assume he’s white. I think that’s very telling.”

“Yes,” said the professor. “You see how language is imbued with this idea of the ‘gaze,’ to borrow a term from Lacan. Whiteness is the standard—everything else is judged as an anomaly.”

At this point, I suggested that maybe statistics also had something to do with it—because, on our predominantly white Midwestern campus, black people were an anomaly. Statistically, the poor victim lying on the stairs is more likely to be white—by far. That’s why we assume he is. But if he’s black, that’s outside the bell curve, and therefore maybe worth mentioning.

“No,” the professor insisted, “The point is that these power dynamics are built into the language. Whiteness is the standard.”

So according to him, language itself is racist. This was one of the many moments when I despaired of modern academia.

So what’s so bad about being concerned with the oppression of black people? What’s so bad about a little exaggeration here and there, as in the example above? Shouldn’t we help those who have been unjustly persecuted?

Naturally, it’s good to fight injustice. But there’s more at work here than that. The trouble with setting up one group of people as oppressed and another as oppressor is that the groups begin to see themselves that way. A logical (or rather illogical) extension of this concept then follows: members of the oppressing group are capable of no good, while members of the oppressed group are capable of no evil. Members of the oppressing group have every sort of advantage while members of the oppressed group have every sort of setback. So we coddle the oppressed and condemn the oppressors.

When the relationships between human beings are set up in such a simplistic and artificial manner, it allows for some serious abuses. Because everyone is viewed through the lens of what racial (or other) group they’re a part of, they cease to take responsibility for their actions, or, at least, others cease to view them as responsible. As I’ve been informed many times, I am guilty of racism and other crimes simply because I’m white, even if I don’t know it and don’t want to be. Black people are victims, unable to get ahead, held back by society, even if they don’t know it and don’t want to be, simply because of their skin color.

As a result, it’s very difficult for either of us to take responsibility for our good or our bad actions. Let’s say I get a good job: it’s because I’m white and privileged. Let’s say my black neighbor can’t get one: it’s because he’s black and discriminated against. Hard work and ability aren’t taken into consideration. Or let’s say I hurt a black person in some way. It’s because I’m white. My own, personal, moral culpability is sidelined, even though that’s the real issue, and the guilt of the white race takes center stage. Here’s another example: since black people are part of a protected group, they can appeal to this in order to get things they want, like acceptance into a university or a scholarship. They can play the race card, and universities often take it, rather than examining the person’s actual merits as a scholar. This kind of thing is disrespectful to everyone, blacks most of all.

The irony here is that identity politics recreates the very racism that it claims to be combatting. Many white academics embody the racism they purport to be fighting. White academics will eagerly and readily make blanket statements about races. They will engage in stereotyping. They will hand out racial attacks like girl scout cookies. And they get away with it. The reason? All of this is directed at their own race. Yet it is, after all, the very definition of racism to judge people on the basis of their skin color and not their individual character—even if you share that skin color.

Of course, if it began and ended with irony, I’d be less concerned. But there’s actually a significant danger embedded in all this talk of racism. It is the danger of a self-fulfilling prophecy, if you will. I said earlier that my professor is a neo-Marxist. That means that he’s seeped in an ideology of conflict. In its original form, Marxism was all about class conflict—the bourgeois oppressing the proletariat. The only solution to this conflict, according to Marx, was a revolution that would bring about a communist society where class was erased, and, therefore, oppression eliminated.

Now, sometimes the proletariat doesn’t know what’s good for it, and fails to pursue the communist ideal. So that’s when the party must step in and force the issue. But, even still, some people don’t want to give up all their private property. Some people don’t want all the means of production to be in the hands of the state. This opposition must be destroyed. The result is genocide.

Atheistic Marxism and its offshoots is, hands down, the deadliest ideology ever known to man. It has killed over 100 million people.[i] Every country where communism has been tried—Russia, China, Cuba, North Korea and many others—has suffered, often on a massive scale and with a catastrophic death toll.

Marxism today has taken a slightly new form, but it still surrounds us. Instead of focusing on conflict between classes, it focuses on conflict between society and minority groups. It is social conflict instead of economic conflict. The Marxist formula is simply applied to each of the many victim groups we’ve heard so much about: women, gays, transsexuals, blacks, and so on. They are being oppressed by the structures of society. The only solution? Revolution. Overthrow the current social order to create one that is more equitable.

Talk of oppression—a rhetoric of victimhood—is often a precursor to mass violence and killings, such as in the case of the way people blamed the kulaks prior to the dekulakization and Holodomor. That’s one of the many reasons we should be concerned about the kind of language used in modern higher education. Just imagine the well-justified outrage if the rhetoric of academics began to bear similarities to Nazism. A lot of people would get fired, or worse. Yet when the rhetoric in question bears a very real resemblance to other deadly ideologies, very few object.

We know where this kind of talk leads. One could well argue that that notion of oppressor/oppressed—not the color line—was one of the greatest problems of the twentieth century. We have paid the price in blood. There is no need to repeat our mistake.

Constantly analyzing, discussing, probing and even fabricating conflict between people has a strange effect: it tends to fuel that conflict.

Do racists exist? Certainly. Do groups of people sometimes do bad things to other groups of people on the basis of group identity? Certainly. Should white people treat black people fairly? A resounding yes! But not simply because of their skin color; they should be treated well because they’re human. And they should be judged as individuals.

The real problem is that all this talk about race is simply a distraction. What we need is not more racial tolerance, at least as conceived by modern intellectuals. What we need is more charity. And humility. We need to see others as individuals inherently worthy of love and respect, not members of a victim group or an oppressor group. This only serves to divide people. Only true charity unites. No army of intellectuals and academics can change this reality.

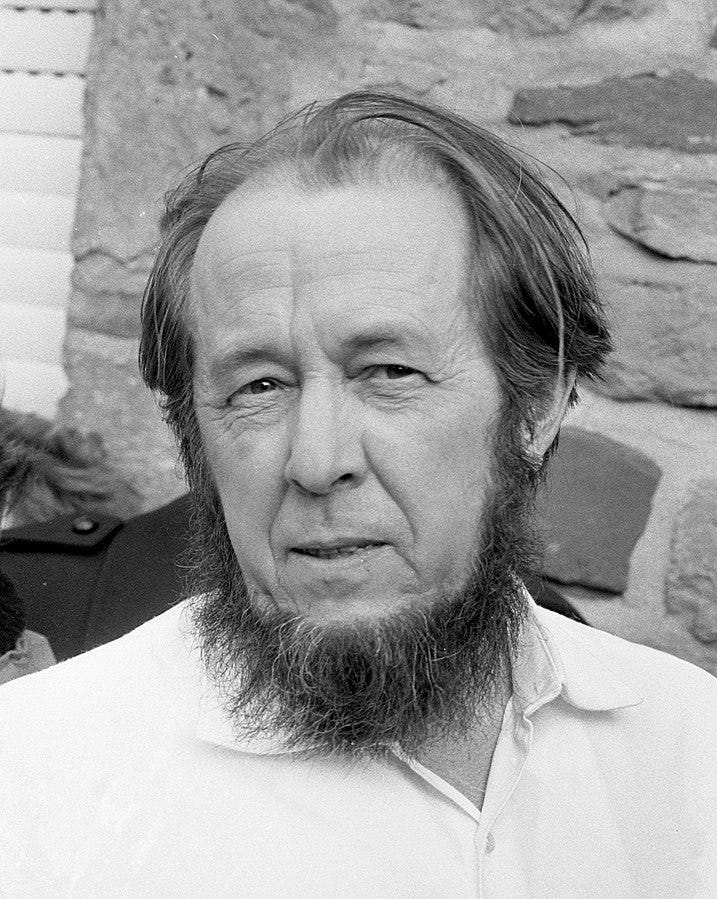

Aleksander Solzhenitsyn knew what Marxist and neo-Marxist ideas could do. He lived through their consequences. This writer spent 11 years in Soviet labor camps and exile. He could have chosen to view the world in terms of oppressed and oppressor—he had certainly lived as member of a victim group. But he knew better.

In the middle part of the twentieth century, fifty years after Du Bois’s color line statement, this is what Solzhenitsyn wrote in The Gulag Archipelago: “If only it were all so simple! If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.”

The problem of the twentieth century does involve a line, but it’s not a color line. It’s that line inside the human heart. Having turned his back on goodness and truth, modern man has nothing to save him from the evil inside himself. That’s the real problem. The solution? Not revolution. Conversion of heart.

[i] Paul Kengor, The Devil and Karl Marx (Gastonia: Tan, 2020), xvii-xviii.