“It is not our part to master all the tides of the world, but to do what is in us for the succour of those years wherein we are set, uprooting the evil in the fields that we know, so that those who live after may have clean earth to till.”

--J.R.R. Tolkien, The Return of the King

Having pulled the starter on the chainsaw a dozen times without success, I finally flung the device from me in disgust and wondered whether promises made to the dying really are binding. The chainsaw crashed into a nearby tree-trunk and disassembled itself with a metallic exclamation. I ducked a flying bolt, and then flopped down onto the ground in exhaustion, running a dirty sleeve over my forehead as I did so. It came away wet with perspiration. The heat and humidity had combined into a sickening blanket of energy-sucking oppression. Still, it was a pretty day, I noted with vague disappointment. Leaf-filtered sunlight speckled the earth around me, and the lonely, clicking call of a cicada sounded in the bushes behind me. The great, comely forms of the trees stretched up around the farmyard, baring their leafy heads to the sky, quite unmoved by my little drama of ineptitude. The yellow, untamed fields showed through the trees. My fields. My withered and wasted fields, lying tumbled together. Beyond these I could see glimpses of the neat, orderly rows of the neighbor’s crops. The neighbor’s fields were not withered and wasted and overgrown. They were small, like mine, but well-kept. Some of the fields had been converted to pasture, and fifty head of cattle browsed them in contemplative bliss, filling the landscape with an atmosphere of peace and order. The neighbor’s farmstead was clean. The buildings were freshly painted. The house was a cheery red and possessed a shiny new metal roof. My house was vomit colored and possessed smashed windows and a rotting porch. It seemed to shed its worn-out shingles like dandruff. My out-buildings were even worse: they slanted at impossible angles, as though they’d been struck by a brutal wind and then somehow frozen in place, halfway to the ground, halfway to oblivion. I sighed and seriously considered weeping.

It was then that Mrs. Hunt made her daily appearance to taunt and berate me. Every day at three o’clock her little red pickup would come bobbing down the gravel road until she came even with my eastern fence-line. Then she would slow down to less than a walking pace and poke her long, skinny nose out the window and peer at me. Truly, she was a master of peering. I thought I had seen old women peer before I met Mrs. Hunt, but it was not so. Those women’s peers were mere shadows in comparison. Mrs. Hunt peered like there was no tomorrow. Mrs. Hunt peered like it was an art form. Mrs. Hunt peered with abandon. She surveyed every detail of me and my dilapidated farm, taking it all in, calculating, measuring, and, of course, judging. It was she who owned that infuriatingly perfect farm next door, that farm that was the Platonic form of all farms. She cared for it with the same kind of aggressive attention and meticulousness that she demonstrated when she peered. So she had every right to judge me and my hopeless, degraded homestead. She had every right. And she knew it.

“Looks like you haven’t gotten much of that brush cleared out yet, then,” she called from her pickup, which was drifting past my property so slowly that it seemed to be stuck in molasses. I grinned, and hoped that my sunburn would cover the reddening of my face. I am a self-conscious person, and being peered at makes me uncomfortable in the extreme, even if I am not the negligent owner of the junkiest farm in all of Wisconsin.

“What did you do to your chainsaw there, David?” she asked.

I glanced at the pile of twisted metal resting peacefully at the foot of a nearby tree. “It’s broken,” I said. True enough. It was definitely broken now.

“Did you get yourself one of those magnets for all the fallen roofing nails like I suggested?” my interrogator pressed.

“Not yet, Mrs. Hunt. I’m still trying to get rid of some of these.” I gestured vaguely towards the trees that were encroaching on the farmyard.

“Yeah, they’re really crowding out your sunlight, aren’t they?”

“Yeah, they really are.”

“And that big one there has branches growing out over the house. You wouldn’t want one of them to fall on your roof.”

“True. Very true.” I scratched my elbow.

“I wouldn’t let that one go too long.”

“Right.”

The truck continued rolling slowly by. The old woman inside continued peering. When I had first begun to work on the farm, Mrs. Hunt had quickly gathered that I was inexperienced, and since then she had offered me no end of helpful hints.

“Are you going to get those windows replaced soon? You can’t do anything with the inside until you get the windows done. Rain water will come right in and ruin whatever you do.”

I turned toward the house and studied the empty window panes as though I had never seen them before. “Yes, that’s a good point. I’ll have to do that soon.”

“Yeah. And then you’d be able to live in the house while you’re fixing it up.”

In all honesty, this had never occurred to me. “You know, I could. It would beat driving out here from town every day. But I guess then I’d have to commute to work.”

“Okay, well you think about it.”

“I will.”

She was far enough down the road that conversation was becoming difficult. The truck engine burped and roared, and in a moment the vehicle was flying away toward Mrs. Hunt’s property. Relief swept over me. I headed for the toolshed. Now that my chainsaw was deceased, I would have to use hand saws until I could get a hold of another one. I put it in a few more hours of hard work with these implements. Then evening came, and it grew quiet. The sunlight hung heavy in the tree branches and trickled over the meadow and past the thicket to pool beside long shadows in the farmyard. I sat alone on the crooked steps of the house and drank a beer from the cooler I’d brought with me. Then I slid into my Buick and headed for town.

Since graduating college a year prior, I worked part time as an accountant for Golden Globe Insurance in Eau Claire. I was considering going full-time. Not for more money—I had a good deal of inheritance to live off for a while—but because I felt I wasn’t getting opportunities for advancement. I needed to commit fully before I could start rising within the company. The trouble was, if I did so, I would never find the time to restore the farm. Even as it was, I found it difficult to squeeze in afternoons clearing brush or replacing windows—the task would only become more daunting if I was working full time as well. These and similar thoughts troubled my mind as I made the fifteen-mile journey back to town. When I got to my apartment, I crashed on the sofa in front of the TV and fell asleep, exhausted from the day’s labor.

The next time I went to the farm was different. It was a cloudy day, and the heavy air was pregnant with rain. Dull gray light lay over the farmyard, and with the additional shade cast from the gnarly trees, it was decidedly gloomy. Even Mrs. Hunt’s cattle across the fields seemed subdued and expectant of disaster. Nonetheless, I unloaded the new windows for the house and leaned them against the porch. I couldn’t let the threat of rain dissuade me. I would get those windows fixed, even if I had to do it in a downpour. I knew that my work schedule would prevent me from returning that week, and every day I left those windows uncovered more damage was being done to the house.

Only one problem: I had no idea how to install windows.

Now, standing with hands on hips, staring at the frames of glass, which reflected the darkening clouds overhead, this truth impressed itself upon me. Of course, I had known all along that my understanding of window installation was limited, yet somehow I had bought the things with the assumption that putting them in couldn’t be that complicated. Now I wasn’t so certain. I marveled at my ability to repeat the same mistake so often: with each new task that the farm presented me, I faced unknown territory, yet I always assumed that I’d be able to figure it out. And always I couldn’t. Only with repeated references to books and websites and Youtube videos could I accomplish anything. The curse of being raised in a city, I suppose. I was out of my depth.

At length, I decided to take a look at the old windows, hoping that I could learn something about installation from how they were fitted. The house was filled with shadow, save where the broken windows allowed in a jagged swath of gray light, which somehow only made the interior feel darker. Broken glass and splinters of wood were everywhere underfoot. An old couch slumped in one corner, long since divested of its stuffing by birds and mice and other nest-building animals. An old mirror still hung on the wall, multiplying the empty, cavernous frames of doorways across the room. My foot struck a tin can which skittered across the floor, sending out a hollow crackling noise against the dark. I jumped in spite of myself. I had, of course, been inside the house before, but rarely. It had about it such a sense of desolation, that peculiar desolation attached to places that were once human dwellings—places of joy and laughter and sorrow—but are now only the caskets of human life, that I tried to avoid going inside as much as possible. Today, however, it couldn’t be avoided. I made a feeble attempt at examining the old window casings and sills, tapping away at them with a hammer, hoping that somehow I would discover their manner of construction. But the windows did not release their secret to so unworthy a seeker as I. In the end, I simply started whacking at them until they fell to bits. I cleared out the old broken glass and severed wood, which was hard and gray from the weather and left splinters in my arm, and then cautiously raised one of the new windows, frame and all, into the hole. It didn’t fit right. I realized that I’d knocked out a chunk of studs against which the new window would be fastened.

I swore under my breath.

As if on cue, I heard the sound of a truck engine idling outside. Mrs. Hunt was making her daily inspection. I stepped out onto the porch and waved. Normally, I would try not to be seen by her, but something about being in that empty house made me seek human contact—even Mrs. Hunt’s.

She peered back at me. “Working on those windows, then?” she asked.

“Well, trying to. I bought some windows and everything, but…well…you know I’ve never actually done the installing part with a window before. More just the…purchasing part. That’s the part I’m familiar with. I’ll just have to keep at it, I guess.”

A little divot appeared in her forehead. The pickup ground to a complete halt, and for several seconds the thin old woman said nothing. She looked to me like a little elf, who had somehow gained command of a pickup, with her sharp features and frizzy hair framed against the darkening sky. I stood uncertainly on the porch, shifting my weight from foot to foot and grinning absurdly.

“Do you want help?” she asked at last.

“Do I want help?”

“Yes. Do you want me to show you how to do it?”

I didn’t know what to say or do. “Umm…”

She turned the wheel of the pickup sharply and a moment later she was pulling into my driveway. She parked the vehicle, got out, and approached me. I stood stiff on the porch.

“Help?” I repeated.

“Yes. I’ll show you how to put your windows in.”

The top of her head barely cleared my shoulder, but I saw now that she stood straight and did not hunch and when she lifted one of the windows it was clear that she was still quite strong. Together, we carried the windows inside. I was still too surprised to know what to say, so I simply followed her directions.

When we had gathered all the windows inside, she said, “You know what you need? Some more light. It’s too darn dark in here to work.” Before I could stop her, she had slipped back outside, hopped in her truck, and went roaring towards her own farm to find some work lights. By the time she returned, the downpour had started. It raked and rattled at the roof and came spitting in through the holes in the windows, pricking my skin, and veiled the landscape outside in a deeper grayness, so that it looked as though a sudden fog had come up.

Mrs. Hunt hung up her battery-powered work lights and examined the situation. To my surprise, she proceeded to tear out more of the woodwork around the old windows, paying no attention to the spatterings of rain that the wind would send in her face.

“We’ve got to clear out these old 2x4’s. They’re no good. They’re not set right for your windows,” she told me.

I got to work beside her, and soon we had two large holes amidst bare studs in the north wall. Mrs. Hunt produced brand new 2x4’s seemingly from the raw shadows outside the flow of the worklight, and showed me how to fit them together to make a new frame. She was not, as I would have guessed based on her daily inspections, a particularly bossy instructor. She just quietly told me when I was doing things wrong, and otherwise left me to my work things out on my own. She herself was a quick and efficient worker—I was amazed at her confidence and ease with the materials. This old woman—nearing seventy, I guessed—was far more accomplished at carpentry than I, so that I felt my inexperience. Soon we had the saddles and headers in place, and shortly thereafter, one entire window framed in. By then the rain was letting up, and the darkness of evening coming over the farmyard.

“We’ll cover the other windows with tarp until we can finish them,” said Mrs. Hunt.

I nodded. As I held up the sheets of plastic that Mrs. Hunt had again produced from nowhere and allowed her to nail them in place, I finally asked her, “How did you get to be so good with carpentry, Mrs. Hunt?”

“My husband was a carpenter,” she said. Then she added, “You can call me Claudia, you know.”

“Right. Claudia. Got it. Thank you. I wouldn’t have been able to figure this out on my own.”

She folded her arms and looked at me. “No, you probably wouldn’t have.”

I bristled a little. It was one thing to say it myself, another for her to agree with me. And, as usual when I bristled, I found myself making excuses. “Yeah, I’m really not a country boy. Born and raised in Milwaukee, actually.”

The divot appeared in her forehead again. “So what are you doing out here? Thirty years I drive by this place and watch it fall apart, and then suddenly one day there you are, blundering around making a fool of yourself. I couldn’t believe my eyes.”

I hesitated. Her gray eyes glinted and did not waver from my face.

“It’s not my choice, actually. I feel totally out of place here. But I have to try to fix the place up. It was a promise I made.”

“A promise?”

“Yeah. A promise.” My eyes lowered to the floor, weighed down by memories.

“A promise to whom?” she pressed.

I laughed a little, not knowing why. It sounded odd and hollow in the darkening room. Then I let it all out. “My dad. As he was dying of cancer. He used to own this farm, back before I was born. But when big agriculture came, he couldn’t keep in the game. He couldn’t keep up with the new industrial-type farming. Not with his traditional methods—which of course he wouldn’t change. So he lost the farm. He asked me to buy it back with some of my inheritance and fix it up.”

Silence.

“His dying wish?”

“Yes. Reclaim the land, the house. Fix it. That’s what he wanted me to do. That’s what I promised.” I realized with some surprise then, that I had just told her of that moment, that moment beside his deathbed, that moment of intimate endings and beginnings.

“Your father was a wise man. I always thought he was, but now I know.” She spoke with decisiveness.

My brow curled down in confusion. “You knew him?”

Her eyes seemed to stare past me, into the darkness or maybe the light, burning softly like distant candles. “No, not really. I didn’t know him. But I saw him. I’ve been driving by this farm for many years. When I first bought my place there was a man and his wife living here. He took good care of this place. But after farming began to change, one day there was an auction here. Your father had to sell everything and move away.”

This was hard—hearing this so soon after the parting. My brow furrowed deeper and I looked down at my boots. “Did you ever talk to him?”

“No.”

“To her? My mom?”

“No.”

I just nodded dully. “I see. I just wondered.”

“Where’s your mother now? Why hasn’t she come to help?”

“They divorced when I was young. I lost touch with her.”

“I’m sorry.” Then she said, “I’m going to go home now.”

“OK. Thank you for all your help and—the memories.”

She squeezed my arm gently, just exactly the way kind old women do, whose hearts are too overflowing with goodness to bother with personal boundaries. I watched her go with quiet wonder.

* * * *

Days drifted one into the next. The office at Golden Globe Insurance became my world for the following week. Two of the full-time accountants were on vacation, so I had to fill in for them. I spent long hours working on depreciation schedules, sleeves rolled up to the elbow, tie loose, only breaking to retrieve another mug of sludgy coffee.

The office was much like any other, I guess. Enormous rooms filled with cubicles. The quiet shuffling of papers. Someone coughing. Everything was square and painted some shade of gray. A fake plant stood in one corner, next to the table with the coffee maker. I did my best to avoid the other workers. I kept my head down in my cubicle (literally) to avoid notice. I would wait until the little knots of conversationalists moved away from the coffee maker and then make a swift, tactical approach, hugging whatever cover was available. Then, like a master burglar, I would quickly pour another mug, check my 6 o’clock for any signs of observation, and slide away back to my cubicle. I’m not afraid of people. My coworkers just rarely occur to me, and when they do, I try to think about something else.

I used to try to talk to my them. Bill was funny. Jack was super smart. Rachel was formidable. But I would get this strangest feeling when I talked to them that they were just a little bit dead. Just a little bit. Slightly cadaverous. Sometimes the thought was so creepy that it would make me laugh. That usually ruined the conversation. So in the end, I stopped. I felt more alone in the office than when I was in my apartment or out working on the abandoned farm house. I couldn’t explain it. So instead I focused on my work, which I greatly enjoyed, and which I was very good at. My boss, Mr. Rey, would look over my reports with an approving squint, nod a little, and tell me it was very fine work. I had a strong feeling that if I were to start working full time, I would be promoted. Yet, every time I considered this possibility, my farm would surface in my mind, oppressive with the endless improvements it needed. It was always an intimidating and depressing thought. I knew that if I took on more hours at the office I would never finish my allotted task of farm restoration. And I had a promise to keep.

* * * *

When my overloaded week was at last over, and I found a chance to return to the farm, I found Claudia there. She was kneeling down in an enormous patch of dirt that was not present the last time I’d been there. She was working quite contentedly and comfortably, as though the property were her own. I jumped out of my car and staggered toward her.

“What the hell are you doing, Claudia?!”

She stood up a bit stiffly. “Hi, David.”

“What are you doing?” I lowered my voice a little. “This, um, this isn’t your land.”

“I planted you a garden.”

“A garden.” I raised my eyebrows at her. “I don’t want a garden, actually.”

“Well, I’m afraid you’ve got one.”

I tried to give a long-suffering sigh and indignant snort at the same time. The result was that I choked and coughed and felt light-headed. “I don’t want it.”

“Why don’t you want a garden? You’re a farmer now.”

I shook my head and rubbed my brow. I suddenly felt very tired. “Because I’m not going to stay here. I’m going to sell the farm, once I get it fixed up. I can’t take care of a garden long-term. And—and—I am definitely not a farmer. I’m an accountant.”

She peered at me, incredulous. “You’re going to sell the farm?”

“Um, yes.”

“You can’t.”

“Why not? And why am I asking you? This is my property, damn it.” I grabbed a tuft of my own hair and scrunched it in my fingers. I wasn’t sure whether to be angry or embarrassed, and it was making me confused.

She blew away a strand of frizzy hair that had slipped down into her face from under her sun hat. “My dear boy, you made a promise.”

I met her peering gaze. “Yes, I promised to buy the farm with some of my inheritance and fix it up. I promised to restore it. I never promised to live here. And I certainly never promised to become a farmer.” I paused and frowned. “Why am I even explaining myself to you? Why does it matter to you?”

“I care about saving old things. And young things, too.”

I looked up at the sky and sighed. Then I looked out to the north, across the fields. The horizon was broken by low-lying hills. They were flecked green and gold, and the shadows of clouds were running over them in mottled patterns like the back of a turtle. Field met field in seems of shrubbery. It was a pleasing pattern. The whole view was not dramatic, really, but it was quite peaceful. Finally, I turned back to the little old woman standing in my new garden.

When I spoke again, my voice was less distraught. “Claudia, I have to sell this place. I never pictured myself as a country guy. I’m only here for my dad. I’m going to fix this place, sell it, and get a nice suburban house. That’s what I want.”

“You can’t give up on this place! This land, it needs to be healed. Remade. For your father. You have roots here, and you don’t even know it. Who knows what someone else would do with the place?” She gestured hugely with her arms as she spoke, as though trying to encompass the entire property, the county, the state, the world.

“I’m—I’m sorry, Claudia. It’s not me. It’s not the life I’ve planned.”

Claudia looked sorrowful at this. She dropped her arms, and her bag of seeds hung loosely in her hand.

I felt for her. “But—umm—thank you anyway for the garden.”

She looked up, but did not speak.

“I guess, since it’s here now, you’ll have to come over and show me how to tend it,” I added.

She shook her head. “No. You can’t do it right if you aren’t willing to commit. Cover it with a tarp. The plants will die.”

I didn’t know what to say, so I said nothing.

She left soon thereafter, and I turned my attention to tree management. I had bought a new chainsaw, and using this I was able to take down the ill-placed trees over the next few days. My work schedule was light the following week, and I spent afternoons replacing the remaining windows on the farm house. It was slow and difficult work, especially without Claudia’s help, but when it was finished, the house looked enormously better. I patched up around the windows and filled in various holes in the walls, so that I soon had the house fairly well sealed-off. The tasks were tedious, and most of the time I didn’t feel like doing them, but I knew I couldn’t give up. Couldn’t give in. I struggled with every step of the process, learning as I went, with many scars, damaged materials, and wasted hours along the way. Nonetheless, over the course of the summer I managed to insulate the house, put up sheet-rock on the main level, and paint part of the exterior. Sometimes, when I worked, I thought about my dad, how he must have performed similar tasks on the place before I was born. He only ever wanted to be a farmer—I knew that even before the cancer came and he made his final request of me. Sometimes, when he had a little time off, he would take me out driving, in the country, and I could tell it meant something by the look on his face. We would just drive, and be quiet, and look out the window.

After I argued with her, Claudia did not come by any more. I saw her pickup drive by when she went to town, but she didn’t slow down. I was strangely pained.

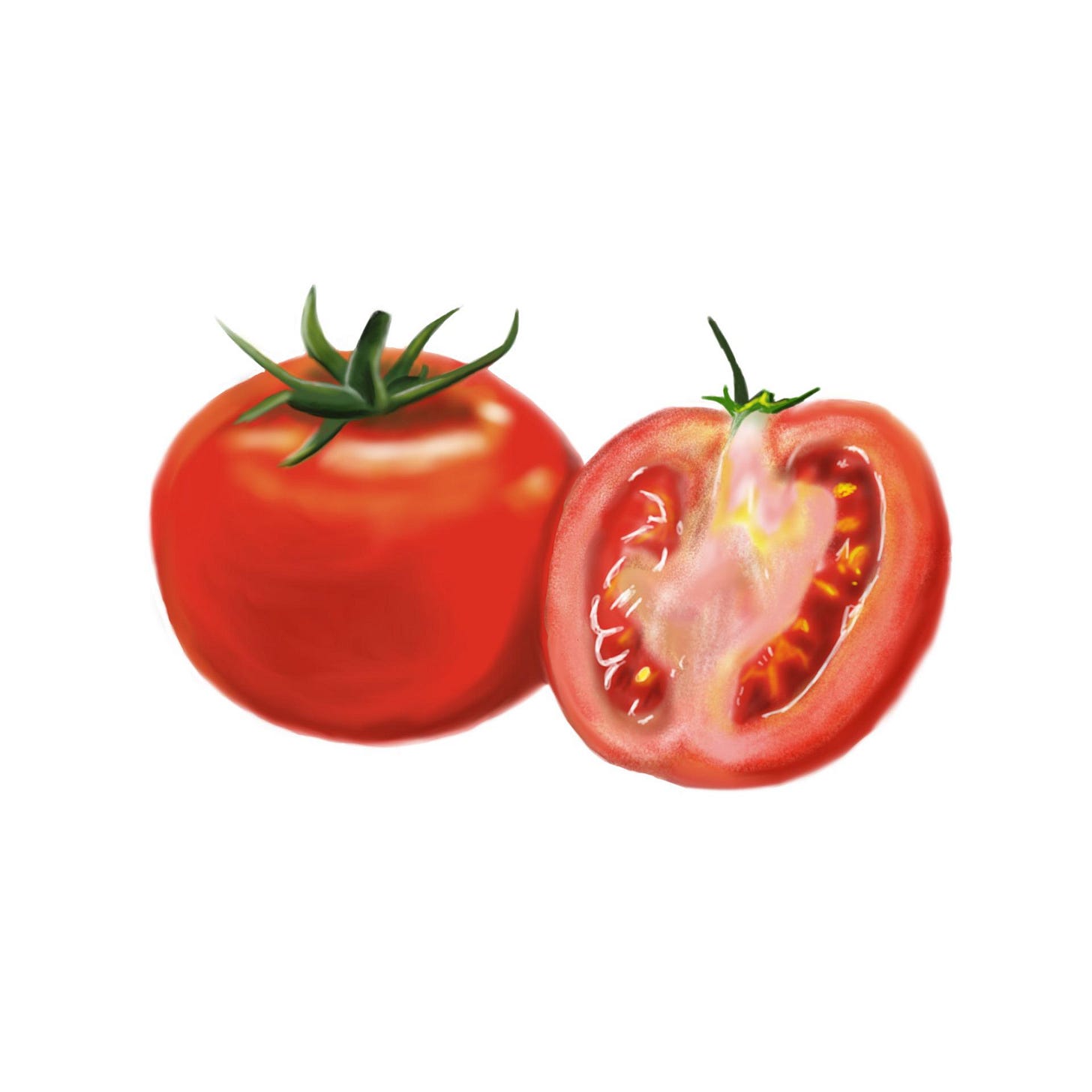

Somehow, I didn’t have the heart to kill the plants in my garden, but I didn’t tend them either, so that by the end of the summer the patch of earth was a gnarl of twisting stalks and vines, rotting vegetables, and groves of weeds. One day, as I pulled into the farmyard, I was struck by how chaotic my garden had become, and so at last I decided to attend to it—probably cut it down, actually, it was so far gone. I walked over to the patch of ground with a massive pair of clippers and studied the plants. I had not the remotest idea which was a vegetable and which was a weed—except for tomatoes. I was able to identify a lot of overripe tomatoes, and some that had fallen on the ground and rotted. I thought I saw a head of old broccoli and a slug-like object that may have been a zucchini. I sighed. It was depressing, all that waste. All those seeds that had been spent for nothing. I poked around in the dirt a while, half-heartedly. In the end, I decided there was nothing worth saving, so I began cutting everything down and throwing it in a pile. But then, as I was cutting down the last of the tomato plants, I saw a glint of pure red among the leaves. I pushed the foliage away, and there was an unspoiled tomato. A late-bloomer that was not yet overripe. I picked it. It smelled clean and fresh like sea-water and moist earth. It was vibrantly alive, amidst all that decay. I set it aside and then finished my work. It was the only edible thing to come out of the garden. A poor harvest. But a harvest.

A thought struck me, then. I finished cutting down the garden, and I carried my pile of dying vegetable matter out behind the house and threw it in the woods. Then I put my clippers back in the chicken coop, which I had converted into a tool shed. I picked up my tomato and set it carefully in the passenger seat of the Buick. I paused. What if it rolled off the seat? What if it got squished? I felt protective of it. So I buckled it in. Then I hopped in the driver’s seat and headed for Claudia’s farm, just me and my tomato.

It wasn’t very far. I pulled into her crisp, orderly farmyard, got out, unbuckled my tomato, and carried it to the house. Afternoon sun blessed the farm with warmth and glimmering light. A breeze carried the tang of cow manure, but it wasn’t an unpleasant smell. The scene was peaceful. I knocked on the creamy-white door and waited. Presently, the door opened, and there stood Claudia, squinting up at me.

“Hi Claudia,” I said, tomato in hand.

“Dave.” She gave me a quick nod.

She hadn’t forgiven me yet, it seemed. I shifted uncomfortably on the balls of my feet. Unsure what to say, I pronounced the obvious. “I brought you a tomato.”

“I see that.”

“It’s from the, um—from my, err, your—garden. It’s all that’s left.”

“I figured.”

“I wanted you to have it.”

She bent just a little at this. Her mouth broke its hard line, and she shooed me in with a fluttering hand. “Oh, come on in, young man. We’ll eat it together.”

“Um, OK.” I followed her into her small and tidy kitchen.

She took the tomato from me and cut it into thick slices on her wooden cutting board. Pink juice spilled out in abundance. She set the slices on a plate, and carried them to the table, gesturing for me to sit. We both sat down and took a slice of the tomato.

I bit into it. It exploded in sparks of flavor. I had never tasted a tomato like it before. It was sweet and ever so slightly bitter and warm and cool and clear and bright. It tasted like spring and stars and salt. It tasted alive. All the other tomatoes I’d ever eaten seemed to me to be mere shadows in comparison.

“Claudia,” I cried, “this is amazing! Why does it taste so much better than other tomatoes?”

“Well, for one thing, it’s an heirloom tomato. It’s not been genetically modified. But even so, it is exceptionally good. You must have good soil. And you just got lucky. Sometimes a crop just turns out better. Sometimes just one specimen will be far better than all the others. I don’t know why. Magic, I guess.”

I took another bite and nodded slowly. “Too bad I let so many of them go. It’s such a waste.”

She smiled. “Maybe. But not a complete waste. This one was saved. And the garden can always be replanted. You can use the rotting plants from this year to make compost for next year.”

“But—” I began, and stopped. I was going to say But I won’t be here next year, but I thought better of it. She seemed to know what I was going to say nonetheless.

She leaned forward and fixed me with her flickering gray eyes. “David, I don’t want to tell you how to run your life, but the tomato has your blood in it. You have to stay.”

“Blood? What do you mean?” I stared blankly back.

She threw up her arms in exasperation. “Don’t you get it? The fields, the trees, the house, the chicken coop, the garden, the dirt. Your father tamed them. His blood and sweat is in them—and now yours is, too. That is not something you can find anywhere else. I don’t care how far you go or how long you look. That is something worth saving.”

I studied her. “I just—I just can’t see myself living on an old farm the rest of my life.”

“Then make it new. Its cycles are your cycles. Its life, your life. Make it an heirloom. Like the tomato.”

A long silence passed. At last, I stood, thanked her, and left.

* * * *

I headed for my apartment, bumping along down the gravel road from Claudia’s house. Evening was coming and darkness falling, but it was the kind of darkness that is warm and soothing and that promises stars. The fields on either side of the road were a rich purple and wreathed in impenetrable stillness. The trees between them were silver and blue in the twilight, full of Arcadian watchfulness. Soon, my own property came into view: the fields, the trees, the house, the chicken coop, the garden, the dirt. In the dark, it didn’t look so bad. It looked more like how it must have looked in the beginning. Like a home.

Without thinking, I pulled into the farmyard and parked. I got out. Stars dusted the sky in pin pricks of light. They showed between the branches of the tree groves. I lay down on my back and watched them. The wind came up again. I thought I heard footsteps, but they were only twigs shaken loose and falling on dried leaves. I closed my eyes.

* * * *

In the morning, I gave my notice to Mr. Rey.

It's not an O. Henry story, but ends in surprise. I just knew that Claudia was Dave's long lost mother. She has the right combination of age and wisdom to mentor Dave to make his own decision for what is more important in life for him. This young man was smart enough to listen and hear, deliberate and choose. Good story.