When many people think of Dante Alighieri’s “Divine Comedy,” they think of popes stuck upside down in burning holes or demons skewering sinners with pitchforks. It may come as a surprise to learn that “The Divine Comedy” is actually a poem about love—yes, even in its first, ghoulish part, “The Inferno.”

Unfortunately, many readers find Dante’s lurid description of hellish torments to be the most interesting part of the work. Few go on to read the second and third parts of the poem—“Purgatorio” and “Paradiso”—since they lack these more visceral elements. But to really understand the poem we must follow the pilgrim Dante on his entire journey—through hell, purgatory, and heaven.

Virgil and Dante

While gorgons, serpents, and the monstrous figure of Lucifer chewing on sinners may fascinate readers, they’re not the real substance of the poem. Again, it’s a poem about love. The state of the souls in hell is meant to show what happens to human beings when their love becomes perverted or misdirected. Dante knew that at the core of our being we act out of love, and that love can either be reasonable or unreasonable, pure or impure. Dante’s long journey through the afterlife is meant to purify his love.

One way that Dante’s heart is purified and the central theme manifests is through the theme of friendship that permeates the work. Dante’s masterpiece famously begins with the lines, “Midway upon the journey of our life / I found myself within a forest dark, / For the straightforward pathway had been lost.” Often called “Dante the pilgrim” to differentiate him from the real-life Dante, the poet, the narrator has lost his way and wanders in dark, brambly valley, where he is soon confronted by a number of wild animals.

Commentators typically interpret Dante’s lost state as meaning that he’s fallen into sin, and the wild animals blocking his path are vices. Indeed, the whole poem is generally read on both a literal and allegorical level, the allegorical one being the soul’s journey to God and to sanctity.

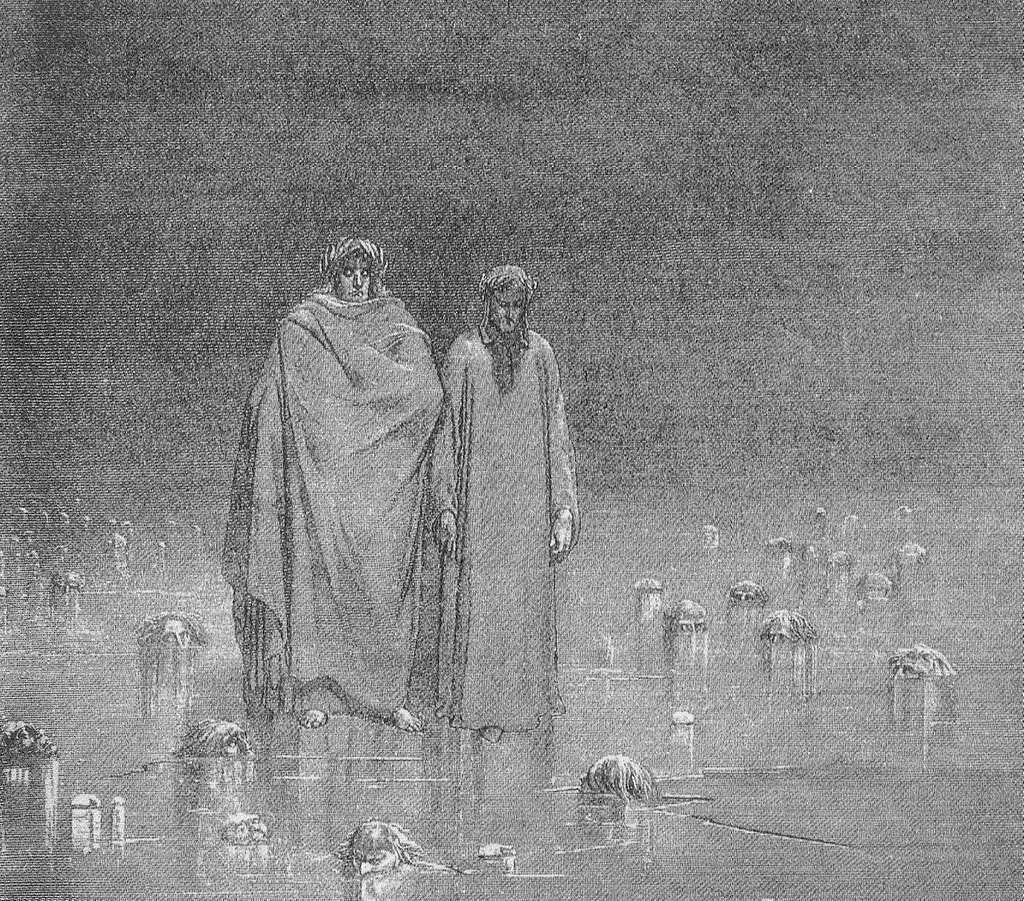

It’s while he wanders amid the clutching branches in the miasmal gulley, unsure how to go on, that Dante encounters Virgil. The Roman poet Virgil (greatly admired by the real-life Dante) becomes his guide and steadfast friend for most of “Inferno” and “Purgatorio.” Virgil tells Dante, “Thee it behoves to take another road. ... If from this savage place thou wouldst escape.”

Virgil has been sent to lead Dante back to “the straight path,” to give him a second chance. This is a pure act of charity. He goes on to tell Dante who it was that sent him: the lady Beatrice. She’s a blessed soul dwelling in Heaven and the one-time beloved of Dante prior to her death. She tells Virgil,

A friend of mine, and not the friend of fortune,

Upon the desert slope is so impeded

Upon his way, that he has turned through terror,

And may, I fear, already be so lost,

That I too late have risen to his succor,

From that which I have heard of him in Heaven.

The very origin of Dante’s epic journey through the afterlife is friendship—beginning with the friendship of his once-beloved Beatrice. Concerned over the state of his soul, she sends the poet Virgil to show Dante the consequences of both sin and virtue in the afterlife.

In “The Inferno,” Dante frequently turns to Virgil for answers to his questions, protection from demons and damned souls, and guidance along the winding paths of that dim, doleful place. While the relationship is one of master-disciple, genuine affection and friendship develop between them as they continue their journey.

At one point, Virgil even offers to carry the weary and frightened Dante: “‘If thou wilt have me bear thee / Down there along that bank which lowest lies, / From him thou'lt know his errors and himself.’”

Dante replies with an equal gesture of goodwill: “What pleases thee, to me is pleasing; / Thou art my Lord, and knowest that I depart not / From thy desire, and knowest what is not spoken.” As critic Paul Krause points out, this beautiful little exchange stands in stark contrast to the selfishness and hatred exhibited by the damned souls surrounding Dante and Virgil.

To Purgatory

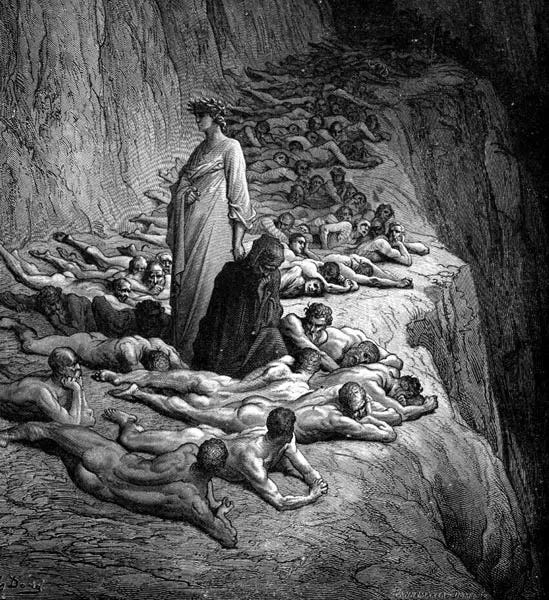

Once they make their way out of hell, Dante and Virgil come to purgatory. In this place, souls who died with some love of God and neighbor in their hearts are purified of any remaining sin and selfishness, their vision cleansed so that they can go to see God. The poet envisions it as a mountain, the opposite of the upside-down cone-shaped hole of hell. The suffering souls make their way up the mountain, practicing penances according to the sins they were guilty of in life.

One of the most striking differences about this second part of the poem is its lighter tone as seen in the degree of love and joy exhibited by the souls here, despite their suffering. Dante sees a boat full of souls gliding toward the island where the mountain of purgatory stands, and all the souls sing a beautiful psalm in unison. Dante soon encounters an old friend, the musician Casella, who used to set Dante’s poems to music. Full of joy, Casella rushes to embrace Dante.

As Virgil and Dante move up the mountain of purgatory, they meet groups of souls suffering certain penances together, but always in a spirit of patient endurance, encouraging one another to persevere. This is the spirit of friendship throughout purgatory—and it’s one of the antidotes to any selfishness the souls may been guilty of in life. The loving communion helps to restore their souls to a pure state. Writer Jessica Schurz commented, “Friendship is central to this story of restoration. For Dante, restoration of the human soul is enabled by the aid of others.”

This is true not just in the afterlife, but in this life as well. It’s possible that souls who showed a greater spirit of friendship wouldn’t have to spend so much time practicing it in purgatory. As Schurz wrote, “We depend on others to accomplish the work given to us, to share moments of joy and love, and to live a fulfilling life—a reality that is easily overlooked in our atomized lives.”

Beatrice’s Example

At the top of the mountain of purgatory, Dante’s time with his friend comes to an end. Virgil, who instructed and guided Dante firmly but lovingly for so long, must leave him. This is because Virgil is not ready to go to Heaven. Instead, Beatrice arrives to be Dante’s friend and guide for the final segment of his journey.

This moment also points to the fact that human reason (represented by Virgil) can only take the human soul so far on the path of enlightenment and the journey to God. At some point, Divine Revelation (represented by Beatrice) must become the guide, taking the soul further than reason alone ever could.

Surprisingly, Beatrice greets Dante rather sternly, calling him to account for the sinfulness and waywardness of his prior life. Like Virgil, she knows that true love and friendship sometimes requires firmness, for the good of the beloved. She accuses Dante of failing to be faithful to her love in the truest sense. Dante wasn’t led by her example to the pursuit of the highest good: God. She tells him,

In those desires of mine

Which led thee to the loving of that good

Beyond which there is nothing to aspire to

What trenches lying traverse or what chains

Didst thou discover, that of passing onward

Thou shouldst have thus despoiled thee of the hope?

In modern English, Beatrice asks Dante why, after her death, he gave up the pursuit of the good and virtuous life that she had urged him to.

Beatrice continues by explaining to Dante how their human love and friendship was meant to resound to the benefit of Dante’s soul:

Never to thee presented art or nature

Pleasure so great as the fair limbs wherein

I was enclosed, which scattered are in earth.

And if the highest pleasure thus did fail thee

By reason of my death, what mortal thing

Should then have drawn thee into its desire?

Thou oughtest verily to have risen up

To follow me, who was no longer such.

Here, Beatrice points out that Dante never saw anything so beautiful and entrancing as she was. But even if this pinnacle of beauty passed away, why did he seek happiness in other earthly things? Her death should have made him realize that true happiness was in eternal things.

Dante acknowledges that she is right. He sees how much he owes to the friendship they shared on earth, since without her, he never would have been delivered from the dark wood at the beginning of his journey. As scholars Aldo Bernardo and Anthony Pellegrini wrote in “Companion to Dante’s Divine Comedy,” “she was truly an inspiration, for his love relationship with her eventually led him to God.”